Six tips for success

- Choose the right ISO for the dive.

- Try to use high F-stops to increase your depth of field

- Try to use fast shutter speeds to avoid blurry sharks

- Train your light meter on a neutral part of the background

- Set your Digital SLR on RAW if you have that option

- If you cant review your images, bracket

Exposure is an equation with three variables. Stay with me, it’s really not that tricky. All you are trying to accomplish is to get the right amount of light to hit the sensor.

The three factors that influence exposure are:

Initially, that may seem like a lot of variables to consider but it condenses down to this: Correct exposure is a balancing act. You want to choose the slowest film speed possible, the smallest aperture possible, and the fastest shutter speed possible, while still allowing enough light into the camera to create a well lit image.

Most people set their ISO first, based on the amount of ambient light available. If you are shooting on a bright day in shallow water, an ISO of 100 would deliver nice un-grainy images. If it is early or late in the day, or if there is a lot of plankton that is lowering the ambient light levels, raise the ISO. Most modern DSLRs are not particularly noisy (another term for grainy) if you shoot up to ISO 800. Beyond that, it depends on the camera. If the light levels change, be prepared to adjust the ISO. Unlike the good ol’ days of film, ISO is now easy to change on the fly, so there is no reason to treat the ISO as ‘fixed’ for the entire dive.

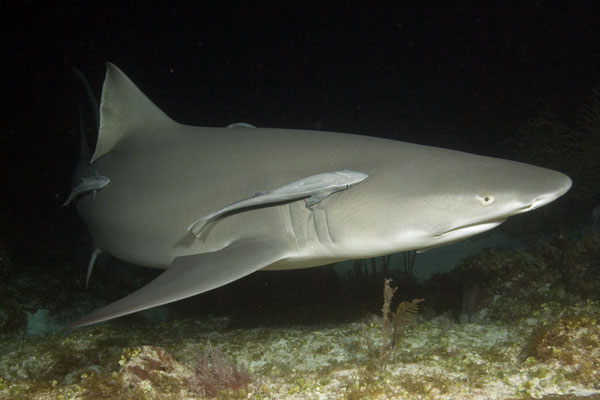

Once you have chosen your starting point for your ISO, as a shark photographer your next priority should be your shutter speed. Different sharks exhibit different behaviors and swim at different speeds. Consequently, your shutter speed will largely depend on the species you’re shooting on that particular dive. For example, tigers move rather slowly and predictably (most of the time) so you can probably get away with a shutter speed of 1/100th of a second. Makos move erratically and swim extremely fast, so you will need a much faster shutter speed to capture a crisp image.

It would be nice if you could shoot makos at 1/1000th of a second but unfortunately, most underwater strobes won’t work at shutter speeds great than 1/250th or 1/320th. So read your strobe manual and find out what its maximum ‘sinc speed’ is. If you’re not using strobes, you can shoot as fast as you like but your images will lack contrast.

Once your ISO and Shutter speed are set, your final variable to set is your aperture. This is where you need to balance your three variables. Remember, you always want about the same amount of light landing on the sensor so that your images are not too bright and not too dark.

If you have a low ISO and fast shutter speed, you are not letting much light in so you will need a wide aperture. Conversely, If you have a high ISO and a slow shutter speed you can probably use a smaller aperture.

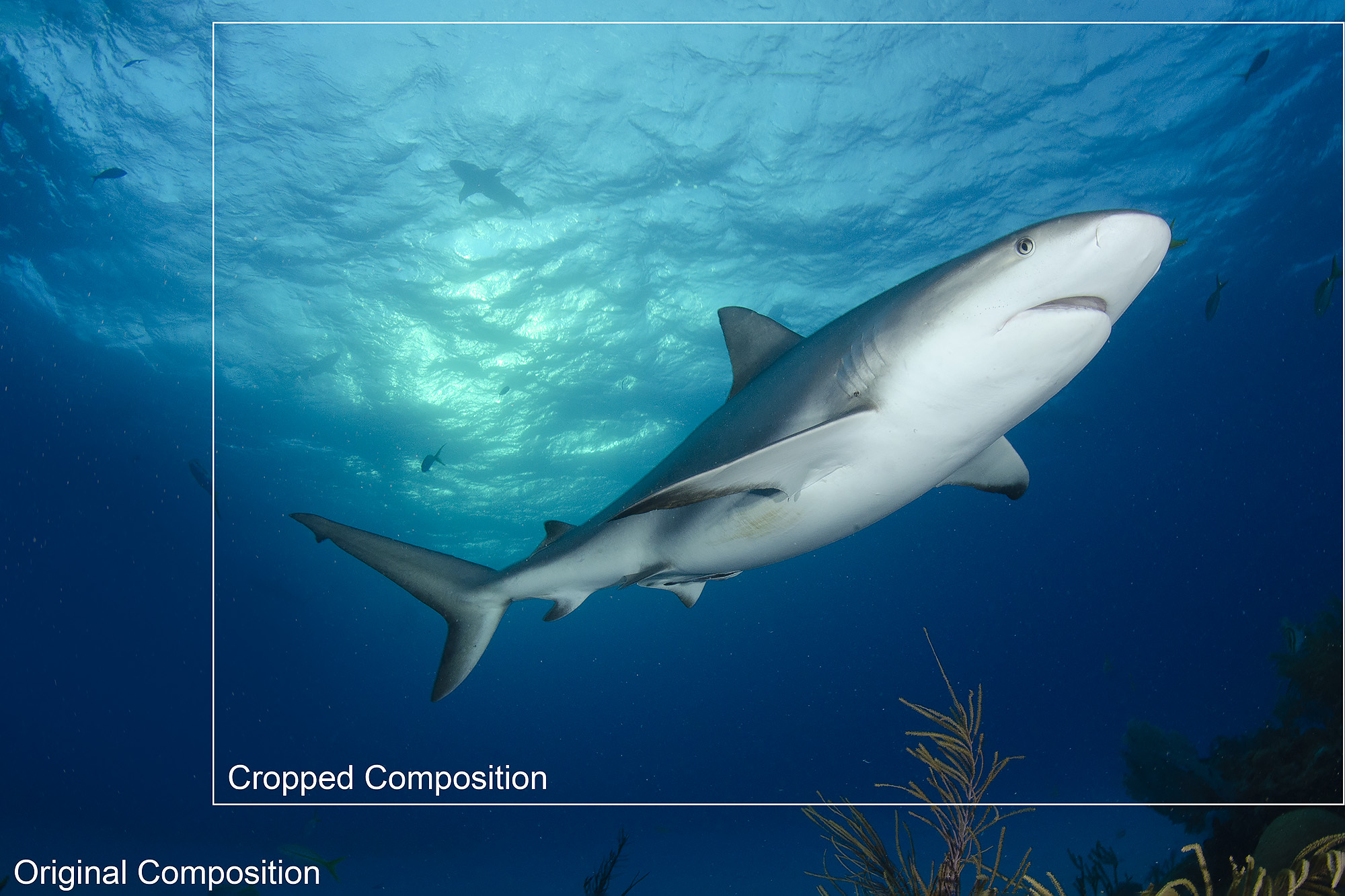

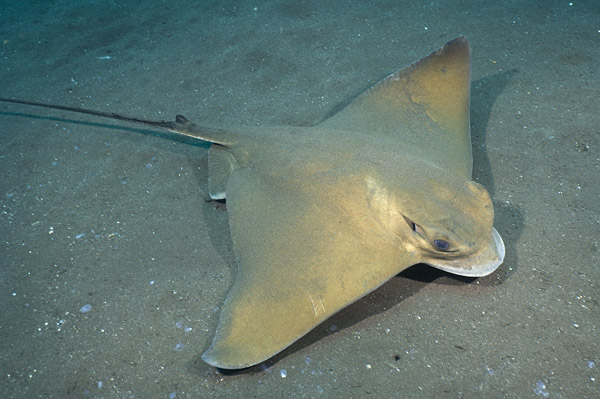

OK, that’s all well and good but it doesn’t give you any real settings advice does it? That’s because the lighting conditions on each dive are completely different. That’s the whole reason for all those possible combinations; so that you can take advantage of different situations. What I can do is show you bunch of images and tell you what I set the camera to in each case and why. That should give you a vague starting point. Remember that you’re trying to expose the background correctly with the available ambient light. This has nothing to do with making the colors show up on your subject which is done using your strobes.

Maybe that gives you a feel for some approximate settings but you don’t have to guess your exposures.

Lots of digital and film SLR’s come with built in light meters and you can buy separate ones for those that don’t. The technology is complicated but using one couldn’t be simpler. All you have to decide is which part of your image needs to be exposed correctly. If you are shooting a shark in the blue then you want a nice blue background and not a shark in the dark. So assuming you have an SLR with a menu, set it on manual and point it at an empty area near the shark. When you half depress the shutter button and look through the view finder you should see a gauge that tells you if your image will be under or over exposed. Often this is displayed as a rule with minus at one end and plus at the other. Now you can play with your aperture and shutter speed until the display indicates that you are on zero (half way along the rule). Now your water will be blue but only if you shoot in that direction. If you move around the light will be different and your settings need to change.

Note: your reading will get screwed up by the sun if you’re pointing straight at it so make sure you’re pointing at the most neutral area of the water with regards to brightness.

Ok now you should have your background exposure dialed in so all that you need to do is light your subject correctly to bring out the color. If you’re unsure how to do this go back to strobe use for a reminder.

Bracketing: What your internal light meter thinks is a good light level might not look so good when you download your pics. Also, they aren’t really designed to work underwater although it shouldn’t make that much difference. To make sure your exposures are correct you can take extra pictures of each shot that are 1 or 2 F-stops higher and lower than your light meter deems appropriate. This is called bracketing. There are obvious drawbacks to bracketing especially for shark shooters. Firstly, you’ll run out of film or memory space three times faster, and secondly, most sharks wont stop swimming to wait for you to adjust your F-stop.

I don’t do a lot of bracketing. I rely on my review screen that shows me a histogram of my digital image. It shows me if any areas of my picture are completely blown out. Be careful when using this as your reference because the back lighting on these little screens often make your images appear brighter than they really are. If you’re more or less on the money, a little tweak in Photoshop will help you get it looking just right.

If you are shooting in RAW (a file type available in all new DSLR cameras) the camera will gather more information than you can see just by reviewing the image. So, in photoshop you can bring out the hidden over or under exposed info until your image looks how you intended it to. There are limitations; you can’t turn a black picture into a brightly lit masterpiece but the RAW file capabilities will certainly help with minor adjustments.

Many pro shooters still bracket believing that it’s better to be safe than sorry.