Common names

Basking Shark.

Binomial

Cetorhinus maximus.

Synonyms

Cetorhinus blainvillei, Cetorhinus maccoyi, Cetorhinus maximus f. infanuncula, Cetorhinus maximus infanuncula, Cetorhinus maximus normani, Cetorhinus normani, Cetorhinus rostratus, Halsydrus maccoyi, Halsydrus maximus, Halsydrus pontoppidiani, Halsydrus pontoppidiani, Hannovera aurata, Polyprosopus macer, Scoliophis atlanticus, Selache elephas, Selache maxima, Selache maximum, Selache maximus, Selachus pennantii, Squalis gunneri, Squalis shavianus, Squalus cetaceus, Squalus elephas, Squalus gunnerianus, Squalus homianus, Squalus isodus, Squalus maximus, Squalus pelegrinus, Squalus peregrinus, Squalus rashleighanus, Squalus rhinoceros, Squalus rostratus, Tetraoras angiova, Tetroras angiova, Tetroras maccoyi.

Identification

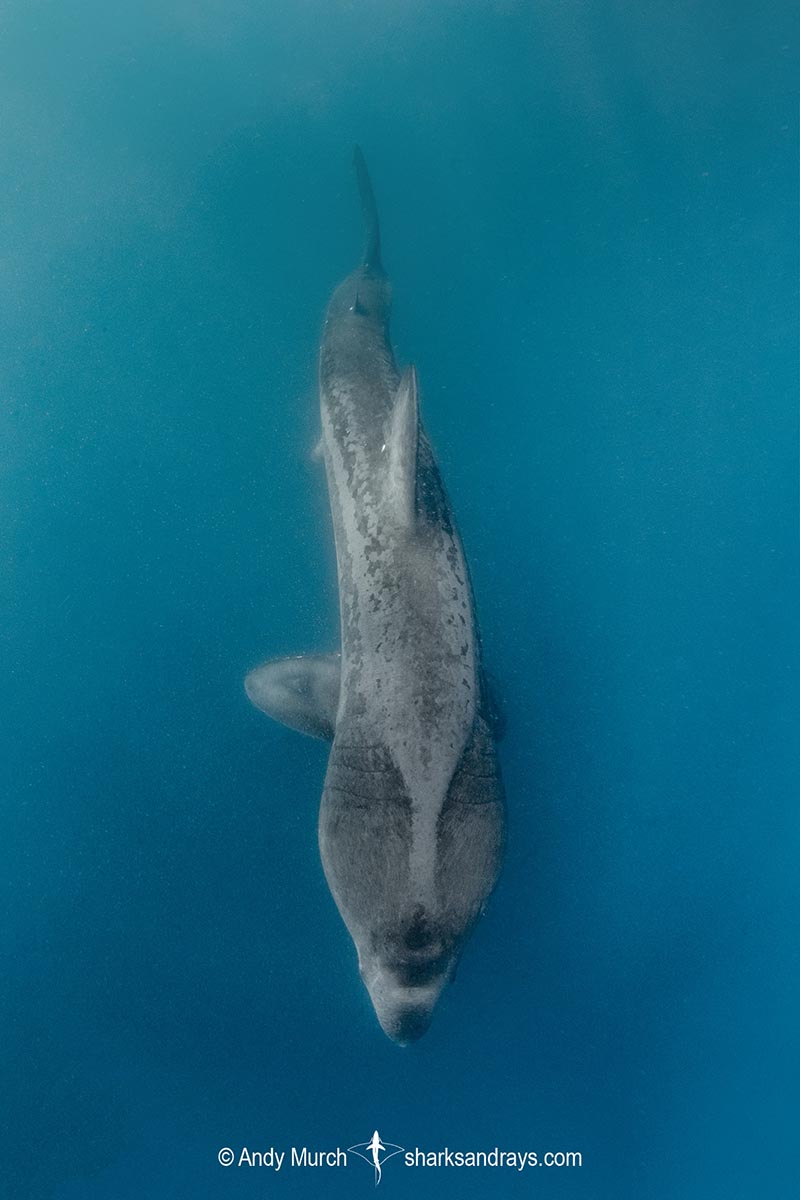

Enormous size. Unmistakable cavernous mouth (when open). Snout tapers to a rounded tip. Eyes small. Gill slits very long. First dorsal fin large with a mildly convex posterior margin. Long pectoral fins with convex posterior margins. First dorsal fin origin level posterior to free rear tips of pectoral fins. Second dorsal fin small; same size as anal fin. Prominent caudal keels support a large, powerful caudal fin. Well developed lower caudal lobe approx half as long as upper lobe. Upper caudal lobe has a small subterminal notch close to tip.

Dorsal coloration slate grey, greyish-brown, or almost black, usually with two irregular lighter flank stripes. Ventral surface usually paler, sometimes with irregular light blotches.

Size

The basking shark is the second largest fish in the world, exceeded only by the whale shark. Maximum length at least 10.4m. Size at birth 150-170cm.

Conservation Status

ENDANGERED

Although there are no longer any targeted fisheries for basking sharks, the population was decimated in the mid to late 20th century. Their recovery has been hampered by an extremely low reproductive rate and high age at maturity. Basking sharks are still caught as bycatch in trawl, trammel nets, and set-net fisheries, and becomes entangled in pot lines. Their large fins are extremely valuable in the fin trade; sometimes as trophy fins which are displayed in restaurants rather than utilized for soup.

Although the basking shark population has been drastically overfished with reductions close to 80% in the North Atlantic and virtual extinction in the North Pacific partly due to an eradication program in western Canada, the remnant population appears to have stabilized, with some signs of recovery in the Northeast Atlantic. Unfortunately, the demand for basking shark fins remains very high.

Habitat

Cold to warm-temperate seas. Usually seen from close inshore to the edge of the continental shelf but known to migrate at great depth across oceans. Surface to at least 1264m.

Distribution

Found throughout the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans but largely absent from the Indian Ocean except off Western Australia.

Reproduction

Despite thousands of basking sharks being caught in directed fisheries in the 20th century, almost nothing is known about the basking shark’s reproductive cycle because no gravid females have been examined. Matthews (1950) demonstrated that the basking shark has a lamnid type ovary. Lamnids are largely oophagous (embryos live on unfertilized eggs) but this would mean a dramatic dietary shift to a plankton based diet immediately upon birth.

Diet

Basking sharks are ram feeders, consuming plankton (mostly copepods and other small crustaceans) which collect in their modified gill slits as they move forward. Periodically, the sharks close their mouths and swallow the build up of plankton. They are occasionally seen skimming the surface with mouths agape, possibly feeding on positively buoyant fish eggs.

Behavior

Basking sharks are known to undergo vast oceanic migrations. During the summer months, they are often seen close to the coast, probably feeding on shallow plankton blooms that are created by the summer sun.

Reaction to divers

Easily approached when encountered by snorkelers at the surface. Basking sharks probably avoid the noise associated with scuba. When directly approached by by swimmers, basking sharks generally change direction but do not bolt.

Diving logistics

Up until the 1950’s, basking sharks were abundant off the south coast of the UK and west coast of Scotland. After decades of overfishing, their numbers have been severely reduced and sightings are now unpredictable at best.

The most reliable place to find basking sharks is around the small isles of Coll and Tiree in the Inner Hebredes, on the west coast of Scotland. Sightings are possible from June through August but the most reliable time seems to be mid-July. Operators in Mull and Oban offer single and multi-day trips. Sightings are far from guaranteed.

On the south coast of Cornwall, basking sharks are even more unpredictable but they generally appear earlier in the summer than they do in Scotland. This makes sense as the water in the south warms sooner and brings more plankton for the sharks.

Southern Island and Isle of Man are also historical spots where basking sharks can be seen.

In the northwestern Atlantic, sightings of basking sharks off of Massachusetts and elsewhere in New England seem to be increasing each year. Hopefully this implies an increase in overall numbers.

In the eastern Pacific, random sightings still occur but basking shark numbers in the Pacific are significantly less common.

Similar species

Great White Shark Although white sharks are only superficially similar to basking sharks, they are often confused by boaters and ocean watchers on the coast of the UK. When swimming at the surface, a basking shark’s dorsal fin and caudal fin are visible. A white shark’s tail sits below the water line when at the surface.